Denali Damsels – Chapters 8-10

Rising 18,000 feet from the surrounding tundra to 20,320 feet, Denali, also known as Mt. McKinley, has been called the coldest mountain on earth. In 1969, my dream was to climb this mountain with a team of women.

Rising 18,000 feet from the surrounding tundra to 20,320 feet, Denali, also known as Mt. McKinley, has been called the coldest mountain on earth. In 1969, my dream was to climb this mountain with a team of women. Looking at our expedition flag, I could imagine six Victorian women wearing long skirts and carrying parasols strolling amidst the mighty glaciers of Denali.

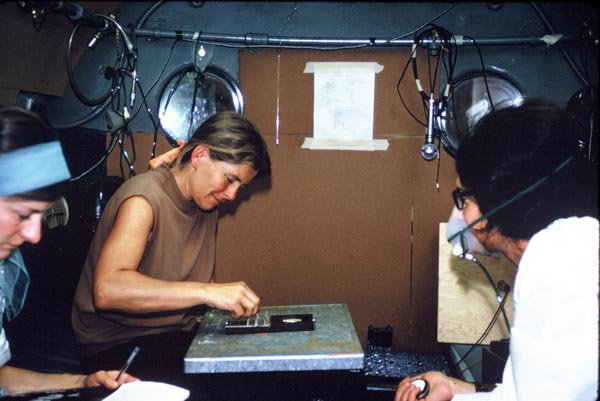

Looking at our expedition flag, I could imagine six Victorian women wearing long skirts and carrying parasols strolling amidst the mighty glaciers of Denali. Before the Denali climb our team met at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks to take part in high-altitude physiology studies. From the left: Margaret Clark, Faye Kerr, Dana Isherwood, Grace Hoeman, and Margaret Young.

Before the Denali climb our team met at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks to take part in high-altitude physiology studies. From the left: Margaret Clark, Faye Kerr, Dana Isherwood, Grace Hoeman, and Margaret Young. During a simulated ascent to 20,000 feet in a pressurized altitude chamber replicating the atmosphere on top of Denali, most of us could still solve complex math problems.

During a simulated ascent to 20,000 feet in a pressurized altitude chamber replicating the atmosphere on top of Denali, most of us could still solve complex math problems. Telling us the weather was suddenly perfect after a week of severe storms, Don Sheldon, our bush pilot, loaded us all on his jeep for an immediate take-off for Denali.

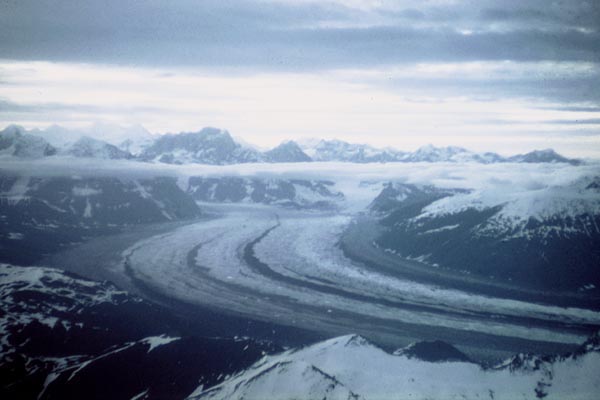

Telling us the weather was suddenly perfect after a week of severe storms, Don Sheldon, our bush pilot, loaded us all on his jeep for an immediate take-off for Denali. The green water sparkling below us solidified into a frozen river of ice leading to the enormous Kahiltna Glacier and the colossal white mass of Denali in the distance.

The green water sparkling below us solidified into a frozen river of ice leading to the enormous Kahiltna Glacier and the colossal white mass of Denali in the distance. I saw the Denali Base Camp below us: a half dozen miniature red, orange, and blue tents and a huge peace symbol someone had stamped into the snow.

I saw the Denali Base Camp below us: a half dozen miniature red, orange, and blue tents and a huge peace symbol someone had stamped into the snow. By 11:00 PM all six of us and our 900 pounds of gear were safely at Base Camp. Trying to fall asleep in the Arctic twilight, I wondered how we'd feel when Don flew us out.

By 11:00 PM all six of us and our 900 pounds of gear were safely at Base Camp. Trying to fall asleep in the Arctic twilight, I wondered how we'd feel when Don flew us out. Our leader, Grace Hoeman, a 48-year-old anesthesiologist from Anchorage, attempted Denali twice and climbed dozens of Alaskan peaks with her late husband Vin.

Our leader, Grace Hoeman, a 48-year-old anesthesiologist from Anchorage, attempted Denali twice and climbed dozens of Alaskan peaks with her late husband Vin. This sunny morning seemed a good time to take the publicity pictures we'd promised sponsors who had donated food and equipment to our expedition.

This sunny morning seemed a good time to take the publicity pictures we'd promised sponsors who had donated food and equipment to our expedition. Margaret Clark, Dana, and I took off our outer clothes and, wearing only our powder blue insulated Duofold underwear, boots, and snowshoes, marched up the glacier.

Margaret Clark, Dana, and I took off our outer clothes and, wearing only our powder blue insulated Duofold underwear, boots, and snowshoes, marched up the glacier. "I dreamed I climbed Denali in my Duofold underwear," I joked, mimicking the old Maidenform bra ads.

"I dreamed I climbed Denali in my Duofold underwear," I joked, mimicking the old Maidenform bra ads. Margaret Clark, a geology student from Christchurch, New Zealand, could carry loads nearly two-thirds of her 100-pound body weight and always wore lady's white gloves.

Margaret Clark, a geology student from Christchurch, New Zealand, could carry loads nearly two-thirds of her 100-pound body weight and always wore lady's white gloves. We stamped back and forth on the surface of the snow, cut the packed snow into two-foot-square blocks, and piled them up to make a wall to protect our tents.

We stamped back and forth on the surface of the snow, cut the packed snow into two-foot-square blocks, and piled them up to make a wall to protect our tents. Faye Kerr from Melbourne, Australia admitted to being 39 years old. Having an extraordinary tolerance to heat and cold, Faye was one of the first women to make climbing her life work.

Faye Kerr from Melbourne, Australia admitted to being 39 years old. Having an extraordinary tolerance to heat and cold, Faye was one of the first women to make climbing her life work. Camped across from us was Mike Bialos's six man team from Seattle. As Faye did her yoga, one of the members of Mike's team did sit-ups in the snow.

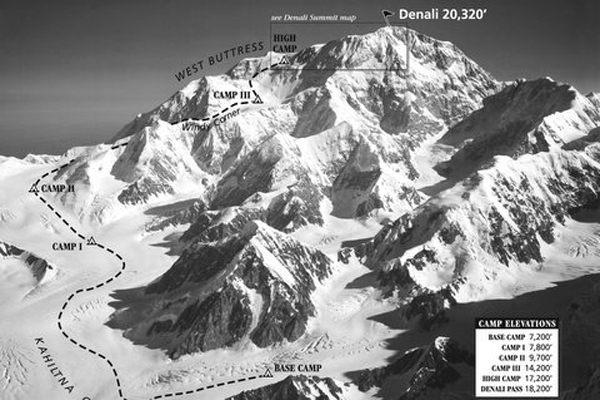

Camped across from us was Mike Bialos's six man team from Seattle. As Faye did her yoga, one of the members of Mike's team did sit-ups in the snow. The Denali map shows the location of the Base Camp and four higher camps we would establish and occupy on our way to the summit. Photo © Bradford Washburn, courtesy Panopticon Gallery 2005

The Denali map shows the location of the Base Camp and four higher camps we would establish and occupy on our way to the summit. Photo © Bradford Washburn, courtesy Panopticon Gallery 2005 During the next days we ferried 700 pounds of food and equipment - about 65 pounds at a time - to Camp II, at 9,800 feet, and then to a cache 2,500 feet higher.

During the next days we ferried 700 pounds of food and equipment - about 65 pounds at a time - to Camp II, at 9,800 feet, and then to a cache 2,500 feet higher. A cloud covered the sun, the temperature plummeted, snow began to fall, and we didn't know which way to go.

A cloud covered the sun, the temperature plummeted, snow began to fall, and we didn't know which way to go. Members of a Japanese ski expedition at Camp III gave us each a bowl of hot Japanese tea that was aromatic, sweet, and much more tasty than the Lipton tea in our food rations.

Members of a Japanese ski expedition at Camp III gave us each a bowl of hot Japanese tea that was aromatic, sweet, and much more tasty than the Lipton tea in our food rations. I went over to the Japanese tent to ask about their delicious tea. With a wide grin the Japanese climber offered me a big red and yellow box of Lipton tea bags.

I went over to the Japanese tent to ask about their delicious tea. With a wide grin the Japanese climber offered me a big red and yellow box of Lipton tea bags. The 2,000-foot, 45-degree hard-snow slope above us was festooned with red, blue, and yellow polypropylene ropes left by the Japanese.

The 2,000-foot, 45-degree hard-snow slope above us was festooned with red, blue, and yellow polypropylene ropes left by the Japanese. I clipped the jumar ascender onto the yellow fixed line, slid it up as far as I could reach, stepped up, and took a deep breath, again and again.

I clipped the jumar ascender onto the yellow fixed line, slid it up as far as I could reach, stepped up, and took a deep breath, again and again. Cresting the ridge at 16,000 feet, I was in a world of brilliant light and ice. Climbing up it was an extreme meditation. Where I placed my foot determined if I lived or died.

Cresting the ridge at 16,000 feet, I was in a world of brilliant light and ice. Climbing up it was an extreme meditation. Where I placed my foot determined if I lived or died. We left our loads at 17,300 feet in a small cave carved out of the ice by a previous party and went back down.

We left our loads at 17,300 feet in a small cave carved out of the ice by a previous party and went back down. The next day our group moved into the cold clammy snow cave at High Camp.

The next day our group moved into the cold clammy snow cave at High Camp. Tomorrow, we would try to summit Denali -- the first group of women ever to make the attempt.

Tomorrow, we would try to summit Denali -- the first group of women ever to make the attempt. What about our leader Grace? Although she was having altitude problems, she insisted on continuing up. Would I be able to send her down if necessary?

What about our leader Grace? Although she was having altitude problems, she insisted on continuing up. Would I be able to send her down if necessary? We began our climb at 4 AM in the Arctic dawn, following faint scratches in the ice left by Mike Bialos's team. My fingers, nose, and forehead ached with the cold.

We began our climb at 4 AM in the Arctic dawn, following faint scratches in the ice left by Mike Bialos's team. My fingers, nose, and forehead ached with the cold. In the late morning, the wind dropped, and the sun changed from a pale disk to a fiery ball.

In the late morning, the wind dropped, and the sun changed from a pale disk to a fiery ball. As we moved steadily upward past outcrops of pink granite and black basalt, the rock crystals glistened in the hard light. Each grain of snow was distinct and perfect.

As we moved steadily upward past outcrops of pink granite and black basalt, the rock crystals glistened in the hard light. Each grain of snow was distinct and perfect. I followed Grace as we slogged across the interminable snow basin leading to the summit ridge.

I followed Grace as we slogged across the interminable snow basin leading to the summit ridge. Grace crumpled onto the snow, holding her head, her eyes sunken, her face drawn and despairing. She was the team leader and she insisted on continuing up.

Grace crumpled onto the snow, holding her head, her eyes sunken, her face drawn and despairing. She was the team leader and she insisted on continuing up. Margaret Clark and Faye roped Grace between them for the final climb to the summit. We agreed that helping her realize her dream was the kindest course of action.

Margaret Clark and Faye roped Grace between them for the final climb to the summit. We agreed that helping her realize her dream was the kindest course of action. I took our picture on the highest point in North America. We were the first team of women ever to climb Denali.

I took our picture on the highest point in North America. We were the first team of women ever to climb Denali. In spite of my recently broken leg, I reached the top of Denali and a new personal altitude record.

In spite of my recently broken leg, I reached the top of Denali and a new personal altitude record. Grace drifted into unconsciousness and a storm was approaching. I had to become an expeditionary leader in a life or death situation.

Grace drifted into unconsciousness and a storm was approaching. I had to become an expeditionary leader in a life or death situation. We wove a rope around Grace lying on a pack frame so she became a manageable bundle protected by a cocoon of sleeping bag.

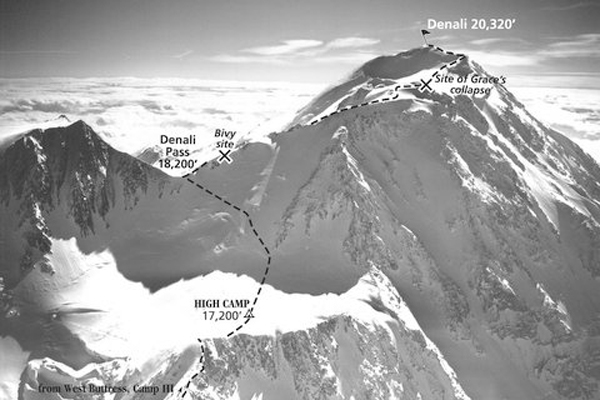

We wove a rope around Grace lying on a pack frame so she became a manageable bundle protected by a cocoon of sleeping bag. The Denali Summit map shows where Grace collapsed and we made the stretcher, where we lowered Grace, and our bivy site. Photo © Bradford Washburn, courtesy Panopticon Gallery

The Denali Summit map shows where Grace collapsed and we made the stretcher, where we lowered Grace, and our bivy site. Photo © Bradford Washburn, courtesy Panopticon Gallery Faye and I chopped a level platform in the ice in the lee of a large gray rock to make a bivy site and put the still unconscious Grace between us.

Faye and I chopped a level platform in the ice in the lee of a large gray rock to make a bivy site and put the still unconscious Grace between us. A few hours later, we managed to get Grace down to the small orange tent at Denali Pass.

A few hours later, we managed to get Grace down to the small orange tent at Denali Pass. Continuing down, we reached our high camp at 17,300 feet. The dank ice cave seemed a sultry haven compared to where we had spent last night.

Continuing down, we reached our high camp at 17,300 feet. The dank ice cave seemed a sultry haven compared to where we had spent last night. The next day the gale drove stinging ice crystals into our faces as we packed huge loads down the ridge.

The next day the gale drove stinging ice crystals into our faces as we packed huge loads down the ridge. As we descended to lower elevation, Grace became stronger. "Get back on the line," she ordered, when I unclipped to take a photo. "It's dangerous to unclip. I'm the leader and if anything happens to you I'm responsible."

As we descended to lower elevation, Grace became stronger. "Get back on the line," she ordered, when I unclipped to take a photo. "It's dangerous to unclip. I'm the leader and if anything happens to you I'm responsible." The wind dropped and the clouds rolled away uncovering dazzling views of the Alaskan Range.

The wind dropped and the clouds rolled away uncovering dazzling views of the Alaskan Range. We snow-shoed down to our tents at Camp III, singing children's songs at top volume. A warm sun shone down on us. We were three days above Base Camp.

We snow-shoed down to our tents at Camp III, singing children's songs at top volume. A warm sun shone down on us. We were three days above Base Camp. Down at Camp II, the storm blasted back. Our tents inflated like willful orange balloons as we fought against the wind to pitch them in the blizzard.

Down at Camp II, the storm blasted back. Our tents inflated like willful orange balloons as we fought against the wind to pitch them in the blizzard. For days we awoke to the roar of a savage wind and many feet of new snow weighting down the walls of our tent. Going out of the tent to go to the bathroom become a heroic ordeal.

For days we awoke to the roar of a savage wind and many feet of new snow weighting down the walls of our tent. Going out of the tent to go to the bathroom become a heroic ordeal. On the fifth morning, we awoke to still air and a cloudless blue sky. Led by the ever-energetic Dana, we made it all the way to Base Camp by that night.

On the fifth morning, we awoke to still air and a cloudless blue sky. Led by the ever-energetic Dana, we made it all the way to Base Camp by that night. The next morning, we were awakened by a distant hum. A few minutes later Don Sheldon landed his Cessna.

The next morning, we were awakened by a distant hum. A few minutes later Don Sheldon landed his Cessna. Flying out I felt centered, serene, and reluctant to leave this splendid domain of ice and snow.

Flying out I felt centered, serene, and reluctant to leave this splendid domain of ice and snow.