Beginnings – Chapters 1-5

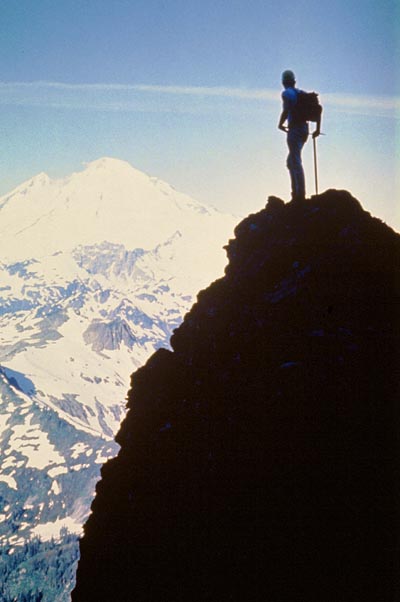

It was September 1964 and we were on our way up Mt. Adams, a stately, 12,276-foot volcano in southern Washington.

It was September 1964 and we were on our way up Mt. Adams, a stately, 12,276-foot volcano in southern Washington. I was an out-of -shape 19-year-old girl from the flatlands wearing borrowed boots and pack. As we headed up, I began breathing so loudly that my companions wondered if I would make it out of the parking lot.

I was an out-of -shape 19-year-old girl from the flatlands wearing borrowed boots and pack. As we headed up, I began breathing so loudly that my companions wondered if I would make it out of the parking lot. As we continued slowly and steadily up the mountain, my body adapted to the unaccustomed exertion, and I began to feel centered and strong.

As we continued slowly and steadily up the mountain, my body adapted to the unaccustomed exertion, and I began to feel centered and strong. Ahead of us was an icefield sliced by long, narrow chasms with walls of blue and green ice — crevasses. It was the most gorgeous place I'd ever been.

Ahead of us was an icefield sliced by long, narrow chasms with walls of blue and green ice — crevasses. It was the most gorgeous place I'd ever been. I sank onto a comfortable rock below the summit of Mt Adams exhausted but content. Right here were the peace and space I'd always craved.

I sank onto a comfortable rock below the summit of Mt Adams exhausted but content. Right here were the peace and space I'd always craved. My first glissade was memorable. Down, down, down I flew for thousands of feet. At first the rough, frozen snow felt cold and uncomfortable beneath me, but soon I didn't feel a thing as the small pebbles in the frozen snow abraded away my thin wool trousers and more.

My first glissade was memorable. Down, down, down I flew for thousands of feet. At first the rough, frozen snow felt cold and uncomfortable beneath me, but soon I didn't feel a thing as the small pebbles in the frozen snow abraded away my thin wool trousers and more. As I lay on my stomach in the infirmary, I dreamed of glaciers and my attempt on Mt. Adams, the best day of my life.

As I lay on my stomach in the infirmary, I dreamed of glaciers and my attempt on Mt. Adams, the best day of my life. I knew the mountains were where I belonged.

I knew the mountains were where I belonged. Five months later, on February 2, 1965, I climbed to the top of Mt Hood, my first mountain summit. I wanted to sing, to dance, and most of all, to hug John.

Five months later, on February 2, 1965, I climbed to the top of Mt Hood, my first mountain summit. I wanted to sing, to dance, and most of all, to hug John. John Hall had first reached the summit of Mt. Hood several years earlier. He broke trail through knee-deep untrodden powder snow to reach the top.

John Hall had first reached the summit of Mt. Hood several years earlier. He broke trail through knee-deep untrodden powder snow to reach the top. And that wonderful spring, I did become a climber.

And that wonderful spring, I did become a climber. John and I climbed Mt. Shuksan.

John and I climbed Mt. Shuksan. We ascended Mt. Hood and Mt. St. Helens by ever more challenging routes

We ascended Mt. Hood and Mt. St. Helens by ever more challenging routes With every climb, I learned more about finding a route through a crevassed glacier, how to read the weather, when to go on and when to turn back.

With every climb, I learned more about finding a route through a crevassed glacier, how to read the weather, when to go on and when to turn back. Every summit was a miracle to me.

Every summit was a miracle to me. Crossing a gulley on the Wy'east route on Mt. Hood, we saw huge boulders thundering toward us. Somehow, we weren't hit. John gave thanks when we reached the top safely.

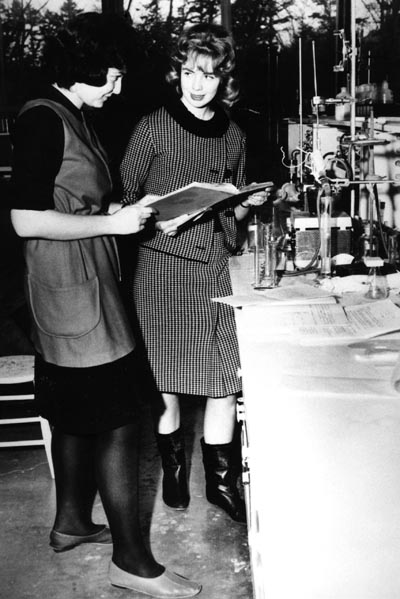

Crossing a gulley on the Wy'east route on Mt. Hood, we saw huge boulders thundering toward us. Somehow, we weren't hit. John gave thanks when we reached the top safely. Both climbing and chemistry opened new worlds for me. Dr. Jane Shell was a brilliant young chemistry professor at Reed. Following her example, all four of the girls in our freshman chemistry class went on to obtain PhD's in chemistry.

Both climbing and chemistry opened new worlds for me. Dr. Jane Shell was a brilliant young chemistry professor at Reed. Following her example, all four of the girls in our freshman chemistry class went on to obtain PhD's in chemistry. Collecting and analyzing volcanic gases was a perfect topic for my senior thesis, combining both my interests. A change in the gas composition can signal an imminent eruption.

Collecting and analyzing volcanic gases was a perfect topic for my senior thesis, combining both my interests. A change in the gas composition can signal an imminent eruption. I climbed Mt. Hood to collect fumarole gases from the summit crater with Dr. Fred Ayres, the chemistry professor who was my thesis advisor and mountaineering mentor.

I climbed Mt. Hood to collect fumarole gases from the summit crater with Dr. Fred Ayres, the chemistry professor who was my thesis advisor and mountaineering mentor. In December of 1965, John Hall and I attempted Popocatapetl volcano near Mexico City, the fifth highest peak in North America.

In December of 1965, John Hall and I attempted Popocatapetl volcano near Mexico City, the fifth highest peak in North America. After reaching the 17,800 foot high top of Popocatapetl, an altitude record for me, John and I collected volcanic gases from the steaming summit crater.

After reaching the 17,800 foot high top of Popocatapetl, an altitude record for me, John and I collected volcanic gases from the steaming summit crater. Then we crossed the valley to attempt Ixtaccihuatl, the seventh highest peak in North America.

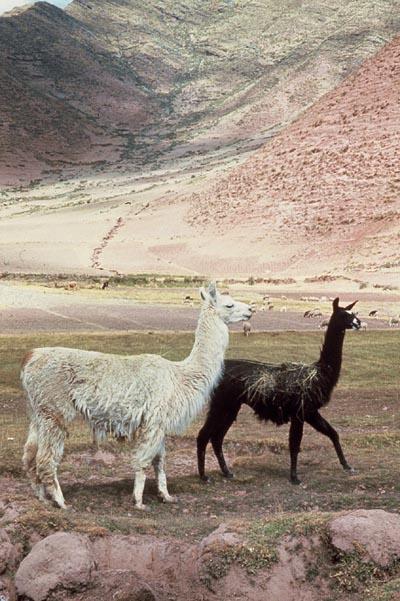

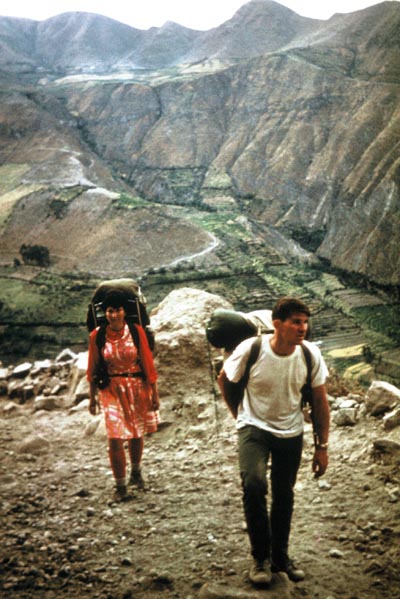

Then we crossed the valley to attempt Ixtaccihuatl, the seventh highest peak in North America. The following year John and I organized an expedition to the Peruvian Andes. First, Paul Pennington and I trekked and climbed near Huancayo and the Inca capital of Cuzco.

The following year John and I organized an expedition to the Peruvian Andes. First, Paul Pennington and I trekked and climbed near Huancayo and the Inca capital of Cuzco. Everywhere we went we were welcomed by the local indigenous people who generously shared with us the little food and drink they had.

Everywhere we went we were welcomed by the local indigenous people who generously shared with us the little food and drink they had. It didn't take long for us to understand the Indians' place as a conquered people in their previous empire.

It didn't take long for us to understand the Indians' place as a conquered people in their previous empire. John and I trekked toward El Misti, the volcano where he'd collected gases.

John and I trekked toward El Misti, the volcano where he'd collected gases. Then, we headed to the Quebrada Llanganuca, a canyon northeast of Lima.

Then, we headed to the Quebrada Llanganuca, a canyon northeast of Lima. Our 1967 expedition to the Peruvian Andes got together in Juaras. From the left: Peter Schindler, John Hall, Bill Ross, and Paul Pennington in front of Huascaran. I'm the photographer.

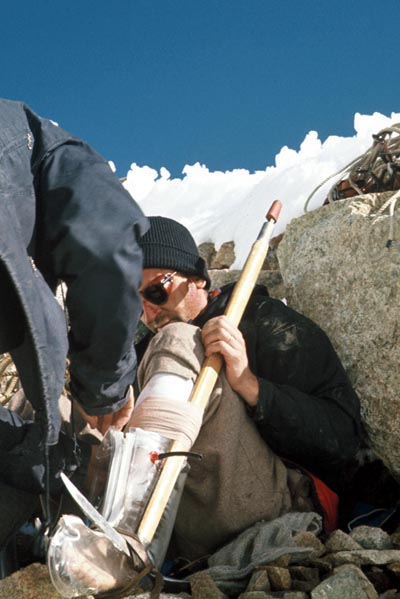

Our 1967 expedition to the Peruvian Andes got together in Juaras. From the left: Peter Schindler, John Hall, Bill Ross, and Paul Pennington in front of Huascaran. I'm the photographer. On our descent from Yanapaccha Norte, Peter fell down a steep gully and broke both his ankles. No one had ever been hurt on one of my trips before, and the way a small error could snowball into a potentially lethal catastrophe was sobering.

On our descent from Yanapaccha Norte, Peter fell down a steep gully and broke both his ankles. No one had ever been hurt on one of my trips before, and the way a small error could snowball into a potentially lethal catastrophe was sobering. For 36 exhausting hours, we took turns carrying the stretcher across the rough mountain terrain.

For 36 exhausting hours, we took turns carrying the stretcher across the rough mountain terrain. While Peter and Bill went to Lima, we attempted Pisco at 19,000 feet. The crux was to cross the crevasse just below the summit. John ran through the treacle-like snow, jumped,

While Peter and Bill went to Lima, we attempted Pisco at 19,000 feet. The crux was to cross the crevasse just below the summit. John ran through the treacle-like snow, jumped, and barely made it across.

and barely made it across. Bill Ross returned from Lima with the news that Peter was recovering and had returned home.

Bill Ross returned from Lima with the news that Peter was recovering and had returned home. With only a few days left to climb 21,000-foot Chopiqualqui, we decided to carry double loads to save time.

With only a few days left to climb 21,000-foot Chopiqualqui, we decided to carry double loads to save time. John found a route amidst the seracs in the Chopiqualqui icefall.

John found a route amidst the seracs in the Chopiqualqui icefall. Getting safely over a large open crevasse on our way to Camp II took more than an hour.

Getting safely over a large open crevasse on our way to Camp II took more than an hour. Every step upward with our mammoth loads was an act of will.

Every step upward with our mammoth loads was an act of will. Most of our team reached the summit of the beautiful 21,000-foot Chopiqualqui in Peru's Cordierra Blanca.

Most of our team reached the summit of the beautiful 21,000-foot Chopiqualqui in Peru's Cordierra Blanca.